Retrogaming: was video gaming better before?

Sat Dec 27 2025

Retrogaming: was video gaming better before?

What can explain this feeling, the one where our eyes widen when we see an intro we haven’t watched in years, a sound we thought we had forgotten but that, in reality, had never left our brain. What explains the fact that 15, 20, or 30 years later, controller in hand, we haven’t lost any of our skill in a game we hadn’t touched in all those years.

Does our nostalgia distort the memories we have of video games? Was it better before? Have we become video game boomers? No suspense here: no, it wasn’t better before, it was different. And perhaps our role, as nostalgics, is simply to pass on a few values that our passion taught us during those pixelated years.

Quality, an inescapable component

Let’s start with the question that rules them all: were video games better before? Sorry to disappoint, but there is no definitive answer, and it would be criminal to say that today’s games are not excellent. Red Dead Redemption 2, the God of War series, the Uncharted games, Clair Obscur — all are masterpieces that fully deserve that title, whether through their music, visuals, storytelling, voice acting, or art direction. When you come out of a game feeling “stunned,” it fully qualifies as a work of art.

However, and let’s not be afraid to say it, the games of our childhood were released finished. No day-one patches, no promises of future fixes. Developers had only one chance to deliver their vision, etched into the plastic of a cartridge or the surface of a CD. This pressure created an extraordinary demand for quality. Each game was a complete work, tested, polished until it shone.

Today, the ability to fix things after release has sometimes diluted that rigor. Modern games are magnificent, certainly, but far too many still launch in version 0.5.

We now see too many erratic or rushed development endings, pushing games out by the date expected by publishers, under the pretext that they can be patched shortly after — sometimes too late. But is it really respecting your audience to release games that aren’t finished…?

Some excellent games even put their studios at risk because of this. We’ll mention only Cyberpunk or No Man’s Sky — both very good today.

Be careful though, and you’ve probably tested some with Recalbox: certain retro games are absolutely terrible, ugly, with poorly designed gameplay. Let’s take the most famous example of all: E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (Atari 2600, 1982)… nothing worked. And to top it off, Atari pulled off a “masterstroke”: they produced more cartridges than consoles sold…

Finally, to conclude this topic, let’s be honest: yes, our childlike perspective distorts our memories. Who hasn’t launched a game, impatiently eager to revisit a childhood gem, only to end up saying: “Ah… that’s not how I remembered it.”

Learning through failure, and accepting frustration

We’re not telling you anything new when we say that games were subject to heavy technical constraints — especially one: space. Consider this: any image of the Super Mario Bros. box art you find online is heavier than the game itself — 40 KB (Super Mario World on SNES was 512 KB, pure luxury!).

This constraint pushed developers to find clever tricks to save space wherever possible, but the most common solution was very simple: for a game to feel long and worth the money, it had to be difficult!

Games back then were ruthless. Not out of sadism, but out of necessity. Technical limitations didn’t allow for 100-hour adventures, so difficulty made up for it. Three lives, no saving, and Game Over. This level of demand taught us something fundamental: persevere, fail, learn, try again.

Every victory was a genuine conquest, earned through sweat and hours of practice. Today, games guide us, reassure us, shield us from frustration. It’s more accessible, gentler — but have we lost along the way that raw pride of truly succeeding?

People often say we no longer tell our children “no” today. Has video gaming reached that point as well?

Why do we play? Today’s pitfalls

Why did we turn on our consoles back then? Ask yourself the question… The answer was simple: to play. To have fun, to try to beat that level, to share a moment with a friend, an older brother, or a younger sister.

Why do we play today, or why do our children turn on their consoles?

Modern games have invented new addictions. Battle passes, seasons, daily challenges that constantly remind us to log in, again and again. Pure enjoyment is no longer what drives our sessions — it’s often the fear of missing out. Competition has replaced pleasure for many players, turning leisure into performance, entertainment into obligation. Games have become services: beautiful but time-consuming, generous but carefully designed to keep us engaged.

Take a look around you: how many children you know have actually finished a game?

This is also due to the overwhelming number of titles available today. If a game doesn’t click, we can instantly switch to another and quickly forget the one we bought just days ago.

Back then, when you had a game, you “wore it out,” because you knew your next one wouldn’t come for months. You had to enjoy it, savor it. And if today you still have your old skills, it’s because you knew that game inside out. That kind of experience has become rare.

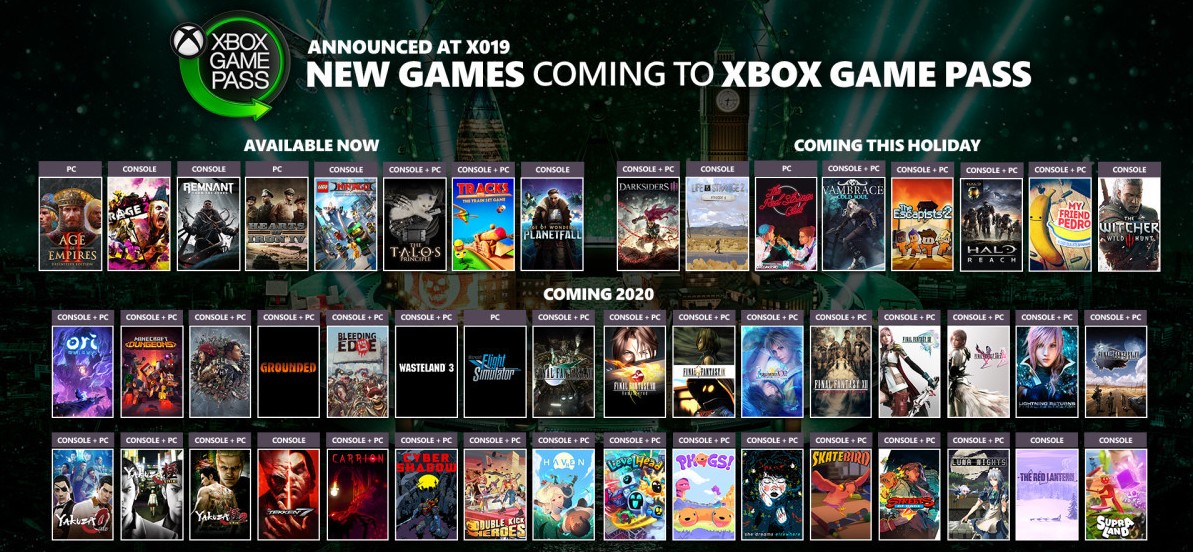

The sheer abundance of titles available today is indecent, and it’s counterproductive in terms of pleasure. Game Pass, PlayStation+, Steam — and more broadly Netflix, Disney+… everything is immediately available, in absurd quantities. Imagine this: many players admit it (and maybe that’s you — no judgment here!), they buy games and never play them.

Think about the absurdity of the abundance of content we have — games, series, films, endless scrolling — and yet we are never satisfied. We always want more. Marketing has won, and never, ever, have we spent so much time staring blankly at content with that deep feeling of never having enough, even though we had far less before.

We didn’t scroll for hours through a library of 500 titles without knowing what to choose. We had our games — the ones we knew by heart, explored down to every corner and secret. That rarity created something precious: time. Time to truly immerse ourselves, to master, to love. Today, abundance gives us everything instantly, but paradoxically, too much choice kills choice. We flit about, download, abandon. This immediacy may have stolen something essential from us: the ability to wait, and therefore to savor.

Playing online or playing together?

There was that sacred ritual: squeezing four people onto a couch, the screen split into four tiny windows, controller cables tangled, sneaky glances at your neighbor’s screen. Shouts, laughter, shoulders bumping. Multiplayer was physical, tangible, real.

Remember that pure excitement: hopping on your bike and pedaling to a friend’s house just to play their game — the one you didn’t have. That different console, that universe you only knew through magazines. Happiness lived in those simple moments, those afternoons spent together in front of a CRT screen.

Today, our children play together without ever seeing each other — connected yet separated, each in their own room, headset on. They have never been so capable of communicating, and yet they have never met each other so little. The paradox of our digital age.

Once again, let’s measure our words: today’s multiplayer games are absolutely incredible (let’s forget battle passes). We all have digital friends whose faces we don’t know, whom we met during a match and never left, spending more time discussing life than racking up kills. These virtual friendships are real — deeply so. They create genuine bonds, shared moments, common memories. It’s not worse than before; it’s different, but just as precious in its own way.

Likewise, it would be disingenuous not to acknowledge the quality of certain multiplayer games, whether in their visuals or their gameplay mechanics. Once again, it’s not worse — it’s different.

We grew up alongside our passion

What makes our generation unique is that we experienced the modest foundations of a skyscraper that now touches the sky. We are the bridge — the generation that didn’t grow up with online play, passes, or DLC. We are the generation that grew alongside this evolution in video games.

We knew cartridges you had to blow into to make them work, scratched CDs that wouldn’t load, handwritten cheat code notebooks, gaming magazines that were our monthly Bible. We grew up with this evolution, living through the digital revolution in real time. Then, gradually, everything became faster, more connected, more complex. We are witnesses of a before and an after.

This nostalgia that sometimes grips us isn’t sad. It’s a bright melancholy — the melancholy of simplicity. Perhaps we feel it because everything has become harder to escape, faster, more demanding. The modern world constantly calls for our attention, bombarding us with notifications, content, endless possibilities. So yes, we remember fondly that time when everything was slower, more tangible, more real in a way.

Photo Michaël Desprez

Photo Michaël Desprez

And our mission is to pass it on. Not to say it was better before — but to preserve that essence, that simplicity in the joy of playing. To teach new generations that you can enjoy a game without fearing you’ll miss a season, that you can lose a hundred times and that it’s okay, that the best multiplayer experiences sometimes happen on a shared couch. Today’s games are extraordinary — more beautiful, richer, more ambitious than ever. But they might benefit from rediscovering a bit of that old philosophy: less, but better. Slower, but deeper. Simpler, but more genuine.

Because deep down, playing has never been about the number of pixels or polygons. It was, is, and always will be about shared moments.

This article is an editorial. It represents a personal point of view and engages only its author.